|

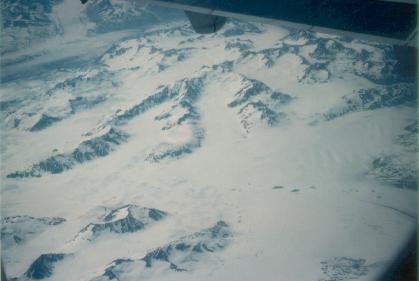

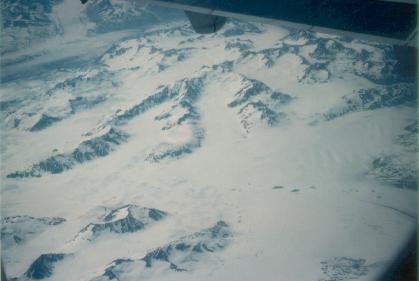

| St. Elias Icefield |

The first order of business was to set up at Fairbanks International Airport's fly-in campground, which is designed primarily for pilots travelling by private plane. I was fortunate enough to be there at a time when an informal aviation safety seminar was held. Three times per week, a volunteer flight instructor visits the campground and shares information with transient pilots about the ups and downs and do's and don'ts of flying in Alaska. Because I was planning to be my own pilot for the first several days of the trip, this was a valuable experience.

Because it was only a week after the summer solstice, and Fairbanks is a mere 120 miles from the Arctic Circle, the 24 hours of daylight called for special techniques in sleeping that night. When light enters the human eyes, it produces a hormone that acts as a stimulant so that a person's biological clock can stay synchronized with the cycle of day and night. The technique, therefore, was to keep my eyes covered as much as possible. Although it was a little harder than usual to get to sleep after first going to bed, it was not difficult to sleep after my eyes had been covered for a while. For most of the night my biggest barrier to sleep was not the 24-hour sunlight, but the noise from traffic on a nearby highway. In the end my efforts were successful; when I got up the next morning, I found an airplane parked near my tent which had not been there the evening before. The pilot had to have taxied in without waking me up.

The provider of the Cessna 172 which was to be my primary means of transportation for the first 4 days was Smith Aero, a 20-minute walk from the fly-in campground where I spent the first night. Early the next morning was my appointment for a checkout, which was a brief (1 hour) flight with one of the agency's instructors, to verify that I'm a competent pilot and to familiarize me with local procedures, tips, and tricks. After completing the paperwork required for insurance, I was on my way.

|

| The Cessna 172 in which I flew myself

from Fairbanks to Bettles, Umiat, and Anaktuvuk Pass |

The Press Toward Barrow

My plan, if successful, was to fly my rented Cessna to Barrow, which is on

the shore of the Arctic ocean; in fact, the peninsula extending out into the

ocean from Barrow is the northernmost point of land in the United States. I

planned to stop in Anaktuvuk Pass, a Nunamiut village in the Brooks Range about halfway from Fairbanks to

Barrow, on either the way up or the way back, depending on what the weather

would allow. Flexibility is an important element of safety in general

aviation; having a contingency plan helps reduce "get-there-itis", a

frequent factor in general aviation accidents because it encourages pilots

to fly in conditions in which they shouldn't.

After noon the day of my checkout, I departed Fairbanks for the two-hour flight to Bettles, a town of 80 residents 150 nautical miles to the northwest on the Koyukuk River 25 miles north of the Arctic Circle. Bettles is often used as a staging area for travel into the Brooks Range. If things went well, I could continue to Umiat, 150 nautical miles farther still, on the North Slope. If not, I could camp right on the field at Bettles.

The flight went well physically, but not psychologically. I was flying over very remote territory in a locale where I had never flown before. The airplane had just one lonely VOR for navigation, and I began to ask, "What will I do if it fails?" Ahead of me were some clouds. I could see through the haze and light rain below them to the sunshine beyond and that they were isolated and temporary. Yet I thought, "What will I do if the weather turns bad?" I had solid answers to all of these questions. I had alternative means of navigation and alternative ways to keep the airplane flying. The fact that I was venturing out alone into an unknown and remote area made me feel uncertain, despite the fact that I had several ways to get out of every conceivable kind of trouble I could get into. At the conclusion of my uneventful flight to Bettles, I elected to remain there for the night and chill out from my irrationally nail-biting flight.

It was now about 4 P.M., and I set up camp literally under the wing of the airplane and spent the remainder of the day stolling around Bettles, which has a few bush flying outfits and a lodge with a restaurant. After discovering that the restaurant was serving a chicken and rice dinner that evening, I signed up. I took a brief walk to the Koyukuk River, where a few floatplanes were moored. I also met a Brazilian couple in a Piper who was travelling to the four cardinal compass extremes of the North and South American continents. The fellow was wearing a khaki shirt which said "Extremos das Americas" in small lettering. The previous day they had been to Wales, the westernmost point on mainland Alaska, and they were now headed for the Boothia Peninsula in Canada's Northwest Territories. Their goal involved only continental land, not islands, or else they would have had to go out the Aleutian Island chain and to the the northern tip of Ellesmere Island in Canada's arctic archipelago. They had already been to Tierra del Fuego, but surprisingly they had not yet been to the easternmost tip of Brazil, their native country. I found this an interesting adventure.

Earlier in the trip, a few pilots had told me that the best flying weather is usually in the A.M. hours, when the sun has not been heating the earth for a while and has not had time to build convection and cumulus clouds. This was especially true in the Brooks Range, which I was to cross on the next leg of my journey north. With that in mind, I went to sleep early so that I could get an early start the next morning. By 7 A.M. I lifted off for Umiat, which was my final staging area enroute to Barrow. Within a few minutes the Brooks Range came into view and the terrain under me became increasingly rugged, eventually developing into the maze of canyons that characterizes the range. On the horizon far in the distance were some jagged peaks.

About 45 minutes into the flight, I made a sudden gasp when I saw a deep notch in the ridge straight ahead. Through the notch I could see flat, open terrain lying beyond.

|

| North Slope |

Upon taxiing into the parking area, I was greeted by a very friendly dog who obviously knew that airplanes carry people; he waited by the door until I got out. After I got out, I was greeted by a swarm of mosquitos. There were no signs of a human being nearby, just several deserted trailers, a couple of quonset huts, and a few fuel tanks. All of the structures were old and rusty. After only a few minutes I couldn't stand the mosquitos any more, so I retreated into the airplane and retrieved my headnet. With that comparative relief, I strolled around the area looking for someone to provide fuel (which Umiat Enterprises had assured me the day before was available). First I noted the main building, a conglomeration of trailers with the spaces between them walled in. The front was adorned with moose antlers. A large sign above the front door facetiously proclaimed, "Umiat Hilton". On the front door was a sign reading "Now entering Umiat, Population 1, O.J. Smith, Mayor".

A few minutes later a young fellow appeared. He said they had fuel, and after checking with his boss told me the price was $5 per gallon. That was a pleasant surprise. Eleven years ago a friend flew here and said it was $4.50 then. Some FBOs in Anchorage had told me that the price per gallon of fuel approaches $7 in some places, and I thought Umiat was remote enough to join that crowd. So I had them top off the tanks, and then I located a phone to call flight service to get a weather briefing for the final leg to Barrow.

The news was not very good. Barrow was fogged in (as it often is), but the forecast was for improvement. So I decided to wait a while and see if that would happen. I then passed some time getting acquainted with the people I had just met. The young fellow's name was Jim, and his supervisor was an elderly man who had lived here for 41 years. We got interested in GPS, so I whipped out the one I had and I demonstrated its features. I learned that despite the native-looking name Umiat, the town was not a native settlement; in fact it wasn't a town at all. It was merely a facility which served as a staging area for guided trekking, hunting and river running trips. The "Umiat Hilton" did have a few accomodations and a kitchen to support these activities. There was also a weather station, and one of Jim's jobs was to monitor it every 75 minutes. I asked how many people lived here, and the answer was that I had just met them both.

An hour and a half later, a second weather briefing showed that the fog in Barrow had broken up into a scattered layer of clouds 300 feet above the ground. Had my aircraft been fully IFR equipped, I would have gone for it. The conditions were similar to those in which I once made a successful instrument approach to Catalina Island. With only the smallest amount of luck, a VFR approach would have been successful also. But there was precious little margin for future change. The slightest worsening would have rendered me unable to get in, so I decided to wait some more. I took a stroll to the Colville River with the dog following me all the way. Upon returning, I called for yet another weather briefing which showed little change from the previous. After weighing the issues for a while after that, I decided with some disappointment to give up on Barrow. It was simply too touch and go. I didn't want to arrive in the vicinity and be tempted to make an unsafe approach. I also didn't want to get in safely and successfully but then get weathered in and not be able to get back out in time to keep the rest of the trip on schedule. Umiat therefore became the most northerly point I have ever reached at 69°22' north latitude.

Anaktuvuk Pass & the Brooks Range

|

| Scenery near Anaktuvuk Pass |

The next day I began preparations for my hike into the Gates of the Arctic National Park backcountry. I was contemplating a two-day trek to the top of Soakpak Mountain (5883'), the first major peak out along a ridge to the northwest of Anaktuvuk Pass. I had taken a close look at it from my overflight the previous day, and from that and a stop at the ranger station I decided that the best route would be up Little Contact Creek, in a fairly narrow canyon, followed by a turn up a bouldery ridge to the summit.

|

| Caribou remains |

For quite some distance I traversed along a steep tundra slope that lined the southwest side of the creek in the canyon bottom. Eventually, however, I was forced to cross to the other side, which I could not do without getting my hiking boots wet. After a total of about 3 hours of trodding, I had covered 3 or 4 miles, gained 750 feet, and decided to pitch camp on a brushy gravel bar by the river. I had somewhat overexerted myself in the bushwhacking and scrambling; because of my lack of experience on this type of terrain, I did not know how to pace myself. A long nap followed. Dinner, to be kept simple, was boiled ramen noodles. I turned in for the night by the clock; being 68° north of the equator and under the influence of the midnight sun, that was the only way I could tell when I was supposed to do so. Because of the very warm temperature (still at least 80°F at 9 P.M.), I took off my clothes inside my tent.

At 10:30 P.M. I was awakened by the sound of thunder and a sprinkle of rain. I had not put the rain fly on my tent, but the rain was too light to justify getting out to do it now. So I drifted back to sleep. At 2:50 A.M. I was awakened by still more thunder. Minutes later the tent was pelted by heavy rain. Though it was daylight, the heavy clouds made it dark enough to enable me to uncover my eyes without blinding myself. I really needed to get the rain fly up this time. In the midnight sun this was not a problem despite the rain. It felt very strange to be doing such a task on a dark and stormy night in broad daylight. Without a watch to check, I could have believed it was 5 P.M.!

When the time came to get up the next day, the weather was clear and calm. After a cold breakfast I headed farther up the canyon toward Soakpak Mountain.

|

| Little Contact Creek near my turnaround point |

The weather was growing gradually cloudier that afternoon as I debated whether or not to fly back to Fairbanks the same day. I gathered some enroute weather information from a pilot who had just flown in on a twin delivering supplies. He said there were a few thunderstorms along the route a short distance out of Fairbanks, but they were small and easily avoided. Other than that, there were no problems. My rational analysis of the facts showed that I had plenty of ways to get out of any conceivable kind of trouble that could happen to me. Although an experienced Alaskan pilot would not have hesitated to make the flight to Fairbanks, I decided after weighing the pros and cons to wait a while. I took my time rearranging my gear, and then I decided to visit the small museum in town. Here I learned about the Nunamiut people and their ingenious survival tactics. While in the museum, I heard a loud clap of thunder followed by heavy rain on the roof of the building. The visibility had dropped to half a mile or less, and the mountains surrounding the village were invisible. For over half an hour I waited in the museum for a respite. The rain eventually slackened a little and, feeling that this was the best I could do, headed out for the grocery store and the gift shop. Before long I was soaking wet, as I had neglected to bring my rain gear, which I finally retrieved from the airplane later. Lucky thing I decided not to fly, you say? Nonsense! Had I decided to go (and left expeditiously), I would have been gone two hours before the storm came. But I don't regret the decision to stay; I didn't have to be back in Fairbanks until the following afternoon, so I might as well use some of the extra slack to feel safer.

Later that evening the storm cleared, a few scud layers drifted across the faces of the mountains, and I spent a while hanging around in the town laundromat, whose warm, dry interior helped dry out my damp clothes.

|

| The Brooks Range |